Remember from your flight training days? Your flight instructor saying (‘yelling’) to keep your feet off the brakes or to put your heels on the ground were amongst the instructions that I would hear at every take off and before every landing. It was both an admonition as well as an encouragement to learn, but it was not often paired with an explanation. And as things go in the aviation training world (or in my other professional world), there is a bit of a ‘see one, do one, teach one’ truth to skill based education and training, and I catch myself now also saying ‘keep your feet off the brakes’ without perhaps going into sufficient detail as to why that is important. I feel I need to explain what might be the consequence of ‘feet on brakes’.

First things first, how do the brakes actually work? This is what the PoH of the club 172 has to say about that. Every plane is a bit different, but this general concept is found in most GA prop planes.

This extremely helpful, and wonderfully descriptive section in the POH does not do a good job explaining the braking system

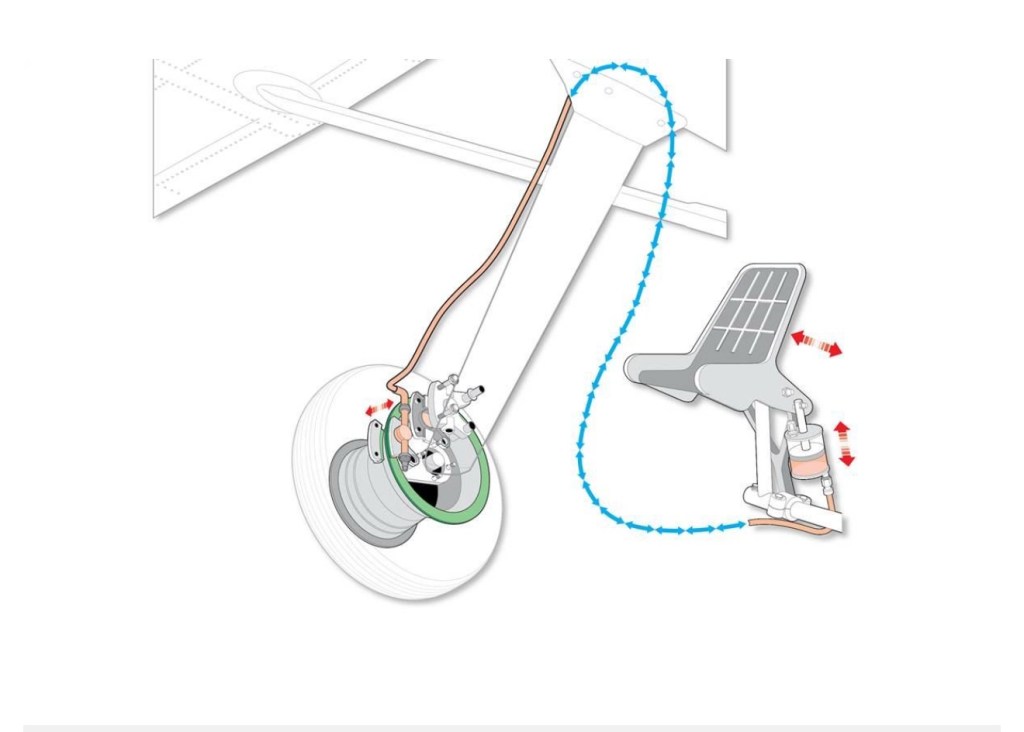

This picture that I lifted from an AOPA article is more illustrative. The article itself is too short and other than ‘be gentle on the brakes’ and ‘don’t ride the brakes‘ does not contain sufficient explanation as to why and what this really means. At the risk of being overly wordy or explaining things that are already widely known, (or even being wrong about certain things!), I will do my best to go over some of this below.

Let me brake (break!) it down into phases of flight. During the pre-flight you check the brakes by looking at the discs, the brake pads, the wheels, the brake lines. It is a hydraulic system. Hydro is a prefix derived from Greek meaning usually water or fluid. A hydraulic system is thus a system that uses fluid to transmit force over a distance. Since fluids are not compressible, unlike gas, the force one exerts on the fluid is the same at the origin of the force, the brake cylinder attached to the brake pedal as it is at the end of the brake lines near the brake pads. Using lever systems the pressure per pound can then be increased on the actual brake pads as those clamp down on the brake discs. This force results in friction and the disc ‘grinds’ to a halt. Stomping on the brakes during preflight thus slams the pedal into the fluid filled small, fragile and expensive cylinder and pressures the fluid, which can’t compress, with that same stomping force into the brake clamping mechanism at the wheel. Stomping thus only serves to test the screws, little axels and cylinder strength unduly, where a gentle ‘squeeze’ would have sufficed just to ensure there is pressure building in the cylinder so as to make sure the fluid column is present between the cylinder and the brake pads. Gentle!

During the walk around the only things you can notice is worn brake pads (black stuff worn thin) or grooving of the brake discs, or hydraulic oil leaking from the brake lines. The grooving of the discs happens as a result of metal scraping metal indicating a worn brake pad which is designed to keep the metal of the brake pad covered. The hydraulic oil (red and oily, in contrast to the yellow to black engine oil) could theoretically leak anywhere along the system. In my experience the two most likely places you might see it is under the plane directly under the brake pedals when the oil leaks out of a cracked brake cylinder, or near the brake line connections at the wheel. So, no stomping on the cylinders and brake lines, it only serves to destroy the cylinders, but checking for the existence of an intact oil column between cylinder and wheel by compressing the brakes gently. Mushy or absent brake resistance indicates air in the system or loss of hydraulic fluid.

The first time this is checked according to the checklist is right before taxi. The ‘I’ve got brakes, do you have brake’s’ discussion between pilot and instructor implies that there is something to check on the instructor side. It is a cylinder on that side as well. In my old Bonanza the co-pilot right sided cylinder was cracked and since it is all interconnected, there was no pressure on the pilot side brakes though. Brake hydraulic oil was leaking on the right side. I question the validity of checking ‘both sides’ for that reason. I guess theoretically oil could have leaked out of the system and air could have snuck in allowing much more compression on one side versus the other. I don’t know. It doesn’t take much time to gently squeeze down the brakes on both sides to test, and as an instructor I like to feel brakes as it conveys a sense of control. By the way, why does everyone stomp the brakes to the point that I worry for a nose dive and a prop strike? Gentle!

Now, we’re taxiing. 5000 ft of taxiway A is a long down hill stretch. You could indeed find the exact subtle pressure to offset with brake friction the thrust you apply by pushing in the throttle to achieve 2300 rpm’s all the way down to the end. The friction at the pads and discs will have resulted in the exact same amount of heat of the fuel that was combusting in the cylinders of the engine, and results in red hot glowing wheels. This is why after a V1 cut, a high speed emergency brake to a stop during a rejected take-off in a jet right before the decision to fly is made (V1, we are flying) is followed by a mandatory cool down time and often a brake inspection before next flight. In a Cirrus SR type plane there is a temperature indicator that will tell on you if you have allowed the brakes to overheat. This is an expensive brake inspection / repair item. The Cirrus, unlike a Cessna, does not have a steering nose wheel thus the importance for symmetrically functioning brakes to maintain directional control and the extra emphasis on brake health in this type of aircraft. ‘Riding the brakes’ to compensate for going too fast can thus result in overheating, wear and tear of the brake pads and discs, and serves to achieve nothing. Pull back the throttle to slow, and only brake firmly and release to allow for adequate cooling in between applications.

Holding brakes before takeoff is good practice. But once you plan to go fly by pushing in the throttle and let go of the brakes, you better let go of the brakes. Heels all the way to the ground and no braking, certainly not in a Cessna. Right rudder (push on the right pedal) but not the right brake to compensate for engine p-factor and steer with the nose wheel steering -not the brakes- to stay on centerline until you go fast enough for rudder authority. This happens well before you reach rotation speed. In the cirrus you will have to use a little differential braking at the very start, no steering nose wheel, and you will get rudder authority much sooner in the take off roll. So feet on the ground, or else you are fighting with the engine and working against your goal of getting airborn. On a short field, this may result in running out of runway.

In retractable gear planes people are taught to tap the brakes before retraction. The idea is that the fast spinning wheel need to be slowed to decrease centrifugal forces when changing the direction of the wheel during retraction, and to avoid heat or fast spinning rubber from folding into the wings. It is a bit of a ‘theoretical’ problem, but good practice. The wheel usually slows down really fast anyway once lifted off the ground. Just look out of your Cessna window and I challenge you to capture a still spinning wheel. Sorry low-wing pilots. You will just have to trust high wingers when they tell you this.

Finally, we are getting ready to land. Captain Incredible is in the left seat fighting the gusts and crosswinds with ample manipulation of the yoke and rudder pedals. The seas are rough and the feet are dancing. The heels are off the ground while demonstrating the learned skill of the aviator, so not to be hindered by the subtle friction of the carpet on the cockpit floor. The landing is nigh and the plane is centered, the side slip and crab are trading places and the wheel(s) touch the terra firma of the runway. A loud squeal of rubber and a jerk of the plane in the direction of the pushed in rudder pedal reminds the pilot of the dual function of the pedal. The wheel and disc were squeezed shut by the brake pad and the moment needed for the wheel to start rolling was not reached. In stead the resistance of the brake pad was higher than the friction on the rubber tire and the wheel did not start rolling. The plane veers off centerline and now the other pedal gets pushed hard because ‘the plane is not braking’ and loss of control may ensue. Depending on the speed of the plane this can result in a runway excursion and bent metal. It takes surprisingly little brake pedal down-force to keep the brake locked. Even more so after a bounce and a slowdown in airspeed as the tire on the runway friction/force is even lower at lower speeds, thus even easier overcome with just gentle pressure on the brake pedals.

There should be no brake action at all when the tires contact the runway so that the wheel immediately will dissipate the rubber friction and the wheel starts rolling. ‘Heels on the ground’ or ‘Feet off the brakes’ is thus crucially important to ensure directional control during landing (remember that the rudder controls direction until you have slowed down well below rotation speed!) and should be maintained off the brakes until the plane has slowed down entirely. Gentle braking pressure is then applied equally to stay straight. Locking the brakes is never a good idea, and should be avoided at all cost. Even when you are about to run off the end, I would rather see very firm but non-locking braking. It is much more effective as it maintains contact between rubber and runway. It is the reason all modern cars and fancy jets have anti-lock braking systems (ABS).

So why write all this? Well, two things can happen when brakes lock and planes come to a stop, even when they make it to the hangar and things are seemingly ok. The first is the most dramatic. The tire may start spinning while the wheel is not. This instantly shears off the insufflation stem from the inner tube and the air is gone. Instant complete flat with subsequent joys associated with that. The other thing that can happen is the tire and wheel both don’t roll. The rubber will get scraped until either the plane stops, the brakes are released or the tire blows. Or all three at the same time. ‘Heels on the ground!’ If not, a traumatic reduction in airplane height above the runway happens and you might be closing the runway down until you get towed off. I hope to use other people’s miserable experience to educate and prevent mishaps like this from happening to those that may read this.

Flat spots like the one below are thus the reason to worry and write. It did not result in mishaps or drama, but it is more than simply expensive wear of a tire. It is possibly an indication of a barely avoided loss of control, a dangerous flat tire on the runway or even an accident. Be careful out there. Keep your feet off the brakes as explained in this article and keep the air in your tires!

Leave a comment