A concept that was made popular in the Bonanza and Baron world by John Eckalbar in his book Flying the Beech Bonanza is ‘Flying by Numbers’. The basic premise is that you no longer fly the plane by the seat of your pants, or based on constant variations in your flight controls and power to accomplish performance with your plane, but rather that you set the plane in predetermined configurations to achieve precisely expected outcomes.

Those who have flown with me know that I like that method of flying very much. During these training flights I explain why I like it, and most are at least polite enough to tell me that they do as well – once they understand what it offers. Taking variables out of your flying makes flying more predictable, and resultantly easier. This is particularly important in situations where one’s brain is already highly tasked, for instance during single pilot IFR flying, but it can help make any flight more enjoyable by freeing brain space. The added benefit is that spotting problems that impact airplane performance, small and large, becomes much more straightforward as well.

So how does it work? In its simplest form, it is knowing three performance or power settings. One for level flight, one for climbing and one for descending. In a Cessna 172 that’s really all that is needed to be remembered. As aircraft get more complex you can add settings that include power (Manifold Pressure and RPM), gear and flap selections for specific phases of flight.

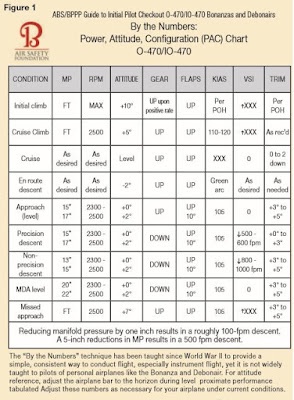

As this table looks a bit overwhelming, I would like to invite you to not let this intimidate you. In fact, I think some of the simplicity of the flying by numbers is kind of lost in some of the well intended messaging around it by the Bonanza Society. Let’s start with our C172 and the three flight regimes outlined earlier. It makes it so much simpler to dive in.

A very safe and stable indicated airspeed in a C172 that allows time to think and act is 90 KTS. It is a good approach speed, a good climb speed and a decent cruise speed when it gets a bit busier or cloudier. The next thing we need to agree upon before finding our power settings is a good decent and climb rate. A very good choice in a C172 would be 500 ft/min. This would allow for a stabilized approach on a glide slope during IFR flights, and a controlled climb through a layer of clouds as well. Our C172 Fly by Numbers table thus has three conditions: climb, cruise and descent, and we need to find the three power settings that correspond.

Level the plane and trim for a 90 kts IAS. Take a bit of time to do this well on a non-turbulent day. Write down your RPM setting / power setting. Do this a couple of times after changing altitude a bit and take the average. On a standard day, with surprisingly little variation in different conditions, the power setting you will find in the club 172 is 2150 RPM. In another 172 this number may vary slightly based on the engine HP, and the drag of the airframe. It won’t be far different.

The next setting is also easy to find. Simply leave the plane trimmed for 90 KTS and out of this level flight add power until a steady climb is achieved of 500 ft/min. It may take a bit for the plane to settle in this climb attitude so let it climb 1000-1500 ft. Perhaps do this exercise a couple of times after descending back down lower, setting up in level flight and adding power again to climb. Note the power setting, which in our club plane will be 2350RPM or close to that.

Finally, we do the same thing for our decent. Out of level flight and trimmed for 90, power is set to 2150 RPMs in the club 172, pulling back the power slowly to start a decent of 500 ft/min at the pre-trimmed 90 KTS will let you find the perfect power setting for this. It will be 1850 RPM in the club plane.

Here are your magic numbers: 1850, 2150 and 2350!

Another way to accomplish this in planes with an autopilot (GFC 500 in the club plane) is to use the autopilot modes to help you make this even easier. Set the plane up in level flight on a heading (HDG, ALT) hold mode and move the power until your IAS is 90kts. Turning off the autopilot (AP) will not do anything. The plane is trimmed for level flight at 90 kts) Turn the autopilot back on if you just turned it off. Then set an altitude 2000 ft higher on the autopilot using ALT SEL and click the indicated air speed (IAS) climb mode. nothing happens until you push in power, and do that until your vertical speed is 500. At this point, you are set to climb at 500 ft/min, so record the power setting (it will be 2350 RPM) As you climb higher and higher, eventually the plane will not be able to climb at that rate anymore and the vertical speed / climb rate will decrease. For the sake of this exercise I am assuming you do this between 2000 and 5000 ft. Lastly, you level back out (click ALT or let it capture altitude after reaching your selected altitude), so you pull the power out to the previously established power required (2150 RPM) back to level flight at 90 kts. Now for the decent power discovery session you set an altitude 1000 ft below your current level and click IAS on the autopilot. The plane will do nothing until you pull the power back, which you will do until you see a vertical speed of 500ft/min. You will be at 1850 rpm in the club plane.

Last step is to verify your settings by doing the above again, but now you use the VS mode on the autopilot and set a 500 ft/min climb and descent, and you move the throttle until you are stable at 90 kts in climb or descent. This power setting should be the same! You now have established your fly by numbers settings. This method works for any plane. You pick your own IAS suitable for flying stable approaches based on your make and model though. For most smaller aircraft / training aircraft I suggest 90 kts but use what your POH tells you to use.

Now, use these settings all the time to get known performance out of the plane. A simple power setting change is all that is needed to go from one flight regiment to another. Flying has become simpler, as you take out variation. This may seem trivial, but it is not. You can focus on procedures or passengers, your scan of flight instruments becomes much less about keeping the plane in a place you want it to be, but rather about recognizing if something is off.

It is important to understand that there is nothing wrong with other air speeds, vertical speeds or power settings. It is entirely fine to push the throttle in fully to squeeze the maximum performance out of the engine and feed it the most fuel possible to get somewhere a bit faster. You could do the same exercise I described above at 100 kts or at 250 or 750 ft / min, and find the numbers that correspond with that. In fact, I would certainly take off with max power and only reduce the power to 2350 in cruise climb. However, using the normal approach speed for your airframe makes a lot of sense for this Flying by Numbers stuff, as departures and particularly approaches are the busiest and most complex times during a flight.

In planes with retractable gear it would be good to understand the impact of lowering the gear on these power settings, or what happens with adding flaps. The beauty of the Bonanza airframe design shines through these numbers: Like magic, if you fly an approach at 106kts, with 17MP and 2300 rpm and approach flaps (10 degrees) in level flight, the effect of dropping the gear is exactly the amount of drag to create a perfect 500 ft /min decent. This simplifies every approach: drop the gear at glide slope intercept on an ILS and the plane follows the glide slope down. Simply magical design! I also don’t think it is by accident that for every inch of manifold pressure change the plane’s indicated vertical speed changes by 100. So, add 5 inches of MP to a Bonanza that is on a GPS glide path with gear down, and it will fly level at the MDA. Simple, elegant and By The Numbers.

I encourage you strongly to figure out these numbers for your plane (and it works for any and all planes) and have them stored away in memory or on a sticky note in your plane. Cessna’s, Cirrus, Pilatus or Pipers, they all can be simplified this way, and some of their organizations have adopted these methods and numbers into their safety and flight manuals. You don’t always have to use them, but once you feel the freedom in your brain during complex flights to get expected performance out of your flying machine, you will use these numbers more and more. It feels great to be monitoring expected flight performance rather than jockeying a bucking bronco, and be far ahead of the plane in your mind.

Feel free to hit me up for an introduction to this Flying by Numbers stuff, and/or leave a comment below!

David

Leave a comment